I was recently asked, “in your view, may Congress regulate the public airwaves or is that beyond the scope of the so-called Commerce Clause?” This question was in reference to the power of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce, given that radio and TV broadcasts are interstate in nature. I started to respond to this question, but then decided it would be much better to write an article covering this, as it brings up a whole slew of issues. The interstate commerce clause is actually a very relevant topic right now with the “Obamacare” law being debated in the Supreme Court, which makes writing this article all the more timely.

I was recently asked, “in your view, may Congress regulate the public airwaves or is that beyond the scope of the so-called Commerce Clause?” This question was in reference to the power of the federal government to regulate interstate commerce, given that radio and TV broadcasts are interstate in nature. I started to respond to this question, but then decided it would be much better to write an article covering this, as it brings up a whole slew of issues. The interstate commerce clause is actually a very relevant topic right now with the “Obamacare” law being debated in the Supreme Court, which makes writing this article all the more timely.

In general, my answer to any question about the federal government’s authority always begins by reviewing the powers enumerated in the Constitution (Article I, Section 8; or any applicable amendment). Is such power explicitly given to congress? If not, then the answer is no, they do not have that authority. This process is supported by the 10th Amendment, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” So let’s look at the question using this process.

The first question that needs to be answered is how to classify the “airwaves”. Are they commerce or are they communication? Obviously, this answer will skew the discussion, so let’s explore both scenarios.

Let’s first take the viewpoint that radio transmissions (whether this is commercial radio, TV, HAM, shortwave, etc.) are primarily forms of communication. Obviously, the founders could not have imagined radio-based broadcasting, so we can’t look for that specifically in the Constitution. However we do find that there is no mention of regulating any form of communication in the enumerated powers or amendments. So we must first accept the idea that the founders did not want communication to be regulated by the federal government. And this idea is supported by the first amendment, where the freedom of speech and the press (which is the closest thing to broadcasting of the time) were specifically protected. So from the viewpoint of communications, the answer is clearly that the federal government can not regulate radio and TV broadcasts.

Next, we consider if the “airwaves” are a form of commerce. Without going into too much detail, I think it is quite a stretch to say that the transmission of radio signals is primarily a form of commerce. For purposes of this discussion, the only real evidence needed is that the “airwaves” can be used for private communication where no commerce is involved at all. But in the strict sense of regulating interstate commerce, ignoring for the moment the spirit of limited government inherent in the Constitution, maybe the federal government could regulate only those transmissions where commerce was being transacted, but no more. And they could only regulate the commerce being transacted, not the underlying technology. But even this very limited allowance of regulation would open a whole can of worms as to what exactly defines the commerce. For example, if I’m listening to the radio, am I engaging in commerce with the radio station? I’m not sending them any money so how is that commerce? If it’s not commerce, then how can it be regulated? Does the simple fact that commerce exists “somewhere” in the operation of a radio or TV station give the government the power to regulate everything around that commerce? If so, that’s a very slippery slope, because commerce exists in almost everything – in effect we could say that there is nothing out of the reach of federal regulation because commerce touches everything.

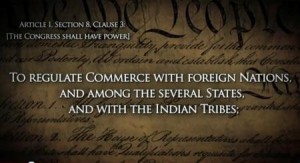

It shouldn’t be shocking that many people do in fact think that nothing is out of the reach of federal regulation. The country has become acclimated to a multitude of government regulations and programs, many of which use the interstate commerce clause as the basis for government authority – predictably creating the very slippery slope scenario that I reference above. But what if we don’t ignore the spirit of limited government in the Constitution and re-examine if the interstate commerce clause does in fact give the federal government the authority commonly claimed? We should start by reading the clause as written in the Constitution, “To regulate commerce with foreign nations, and among the several states, and with the Indian tribes”

Any discussion of the interstate commerce clause must revolve around the basic question: can congress regulate commerce itself, or only the mechanisms of commerce among the states? The whole of the commerce clause begins by giving the federal government the power to regulate commerce with foreign nations, which is to say they can do things like impose tariffs, create import regulations, etc. In other words, they can regulate the mechanisms of foreign commerce. It would be ludicrous to think that this clause gives the United States government the authority to regulate businesses in foreign countries. Continuing in the same clause, they are given power to regulate commerce “among the several states”. Would it not be rational to conclude that in a clause giving power to regulate the mechanisms of commerce with foreign nations, the same clause would also apply similar power to the mechanisms of commerce among the states – not an overarching power to regulate commerce itself?

I would also argue that if this clause were in fact meant to give the federal government the power to regulate people and business, that purpose and those powers would be more explicitly and clearly enumerated, probably in a clause all of its own. The founders were very concerned with the possibility that the Constitution would be construed in ways to expand government power beyond what was enumerated. The entire process that culminated in the Bill of Rights was in very large part due to these concerns. The founders and states were very fearful of big government and making the leap from the Articles of Confederation to the Constitution caused worry that it would create a federal government with too much power. It is easy to see the spirit of the Constitution was about explicitly defining and limiting the power of the federal government. So does it make sense that a clause would be included that gives the federal government carte blanche to regulate business in any way it sees fit? It is no leap of faith to say that the founders had no intention of the federal government getting involved in regulating business. What faster route to oppression than a government that can manipulate and control the economy of a country?

It is often argued that the reason for giving the federal government the power to regulate commerce “among the several states” was so that the states would not create trade restrictions among themselves. By taking this power away from the states, an interstate “free trade zone” would be created, heading off potential conflict between the states as well as encouraging interstate commerce. It was not intended to give the federal government the power to regulate the economy. This argument is bolstered by the fact that it wasn’t until Roosevelt’s New Deal that the interstate commerce clause was extensively used as the basis for far-reaching federal law. Had the interstate commerce clause been intended for overall economic regulation, why did it take nearly 150 years for this power to be exercised (abused?) to the level it has for the last 80?

Faced with this idea, often the next argument rationalized is that regulation of the airwaves is something that the federal government should do, and is in our best interest anyway. To the contrary, it is entirely possible and likely that free enterprise would have solved the challenges of radio communication independent of government regulation, and would have done it much more efficiently and fairly than the FCC. We just need to look at the regulatory-free rise of the personal computer and the Internet for evidence that things like this can happen. But regardless, the argument is largely irrelevant if government regulation violates the Constitution – unless one is advocating ignoring the Constitution, which is the slipperiest of all the slopes.

Any discussion about the interstate commerce clause introduces a host of difficult considerations for many people, as it has so often been used as the basis for federal regulations for the last 80 years. Could the government have been so wrong? Does it continue to be wrong? It is almost too much to comprehend. In order to productively discuss the commerce clause, we must be open to the idea that the possibility exists that government has applied this clause incorrectly to justify past legislation. I’m not asking that you agree that the government has been wrong – just that the possibility exists. Because if you open your mind to this possibility, you also open your mind to the possibility that they may be wrong in the future.